Incorruptible

Complete wireless silence was observed throughout Edgar Whitehead's voyage from Lagos to Cape Town. By the time the SS Calabar arrived in Cape Town it had been posted as missing, believed sunk. The harbor was full, so the SS Calabar tied up to a cargo ship and Edgar clambered ashore over her decks.

As luck would have it, the Naval Officer in charge of movements of military stores was an old friend of Edgar's! Manager of the Land Bank in Salisbury, he had been recalled to Simons Town as a reservist, as he had served throughout WWI in the Royal Navy. He promised Edgar he would personally see to it that his supplies got the highest priority in shipping space.

With this assurance, Edgar relaxed on the long railway journey across the Karoo to Pretoria. There he was met by two officers of the British Military Mission to South Africa waiting for him on the platform. After a smart exchange of salutes they stared at each other in blank amazement. The senior officer, Jimmy Ballard, was an old school friend Edgar had not corresponded with since 1929. The junior, Lawrence Smith, had been Huggins private secretary before the war with whom Edgar had had many a cheerful party in Salisbury after the House (Parliament) rose. They both knew they were meeting a Major Whitehead from West Africa but neither of them had the least idea that Edgar had joined the Army.

Accommodated at the Union Defense Headquarter's Pretoria Club he was presented to the Commander of the Mission, Brigadier Eady and introduced to the Southern African Quartermaster General, Major General Mitchell Baker. There was a coolness between the South Africans and the Mission having different approaches to the War and different social and military customs. Many of the South African Senior Officers were experts at their jobs, but only part time soldiers in peace-time. Some thought the Mission was trying to interfere with their way of running things, though Edgar was sure that feeling was unfounded. They were apt to object if Edgar saluted when entering their offices, and would say, 'Cut out all that nonsense man; let's get on with the work!'

The staff of the Mission went through Edgar's long shopping list and sorted out what items could be obtained from South African military stores from those to be purchased on the open market. As a Rhodesian, the South African Officers gave Edgar every possible help as he went round from office to office. The head of the Medical Corp even supplied the snake-bite serum that was so badly needed in West Africa.

The next step was to buy from manufacturers those items the Union Defense Force could not supply. Edgar had never before been let loose with over a million pounds to spend and welcomed the expert help of the Ordnance Officer of the Mission.

The largest order was for one hundred thousand sets of complete webbing equipment, as the priority was not high enough to be supplied from Britain. There were two firms keenly seeking business, as they had spare capacity. Thankfully, the Chief Ordnance Officer advised him on the relative quality of the samples. But recalling his voyage home on a French liner in 1939, Edgar knew exactly the type of ration wine suitable for the Free French Forces under Britain's command in West Africa.

Other branches of South African industry also keenly sought orders. He found himself much in demand in Johannesburg, being offered by some big business' a two and a half percent commission. They could not understand why he would not 'play ball' with them. At the end of his mission he counted the value of the bribes refused totaled ten thousand pounds!

All these procurements took several weeks. Edgar had kept General Headquarters (G.H.Q.) West Africa fully informed along the way.

But, still outstanding was the most important task; the .303 ammunition the General wanted so badly. Here the Mission was of no use as ammunition constitutes 'War Office Stores'. The War Office would object to drawing on South African supplies. General Mitchell Baker said this was quite outside his province and referred Edgar to General van Ryneveld, South Africa's Chief of the General Staff.

Just then, the whole British Military Mission went to Durban to meet a mammoth Middle East convoy. The morning after they left, Edgar's telephone rang. "You must see General van Ryneveld immediately."

Edgar explained to him, "We are desperate for ammunition."

"I have no authority to decide this. You will have to see Smuts." With that, Van Ryneveld took Edgar through to the Prime Minister (and recently appointed British Field Marshal by King George VI).

Behind closed doors, Smuts said to Edgar, "I have been waiting to see you till the Mission were away because they will be told by the War Office to oppose your request. I am not however prepared to tolerate that anyone shall dictate to South Africa what she shall do with her own production. My right flank is heavily engaged in Egypt and Libya but I must see that my left flank in West Africa is secure. Your General can have five million rounds from South African production."

Mission accomplished, Edgar was given permission to take a week's leave in Rhodesia. Lucky again, he hitched a ride in a Rhodesian Air Force plane.

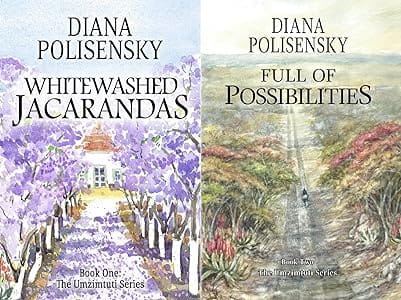

The historical novel Whitewashed Jacarandas and its sequel Full of Possibilities are both available on Amazon as paperbacks and eBooks.

These books are inspired by Diana's family's experiences in small town Southern Rhodesia after WWII.

Dr. Sunny Rubenstein and his Gentile wife, Mavourneen, along with various town characters lay bare the racial arrogance of the times, paternalistic idealism, Zionist fervor and anti-Semitism, the proper place of a wife, modernization versus hard-won ways of doing things, and treatment of endemic disease versus investment in public health. It's a roller coaster read.

References:

- Sir Edgar Whitehead's Unpublished Memoirs, Rhodes House, Bodleian Library, Oxford University, by permission.

- Photo credit: South African Military History Society Journal Vol 11 No 5, June 2000. Article by Andre Wessels, MA, DPhil. Assoc. Professor, Dept. of History, University of OFS, Bloemfontein. http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol115aw.html