Giving of His Very Best

After his first tour of service, as agreed, in August 1942, Edgar Whitehead returned to West Africa following his leave to Southern Rhodesia.

Promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel, his assignment on the Gold Coast was as Assistant Quartermaster General (Provisions) (AQMG) responsible for providing all supplies and stores, whether locally or from overseas.

His eighteen months in Achimota were a strange chapter in his life.

His routine week was eighty-four hours actually at his desk. The heat was extraordinary. He had no private life and no recreations. Work was everything. He had already suffered several bouts of three-day malaria. Taking the yellow dye, Atabrin, a substitute for quinine, as a preventative daily, he was turning yellower and yellower.

A typical hour by hour day started at 0600 when he listened to the first news bulletin in Pidgin English. This was followed by twenty minutes PT–the only exercise he got in the whole day. After a wash under the shower as there were no baths, he dressed in shorts and short sleeved shirt. It was two hundred yards to the office where on the General's personal orders, every officer must be at his desk by 0700. They worked until 0800 when they walked to the Mess for breakfast.

After breakfast, it was back to the office from 0830 to 1300. An hour was allowed for lunch and then work again from 1400-1800. Then to his quarters and another shower to wash off twelve hours of dried sweat. He changed into long trousers and mosquito boots, according to medical orders and walked over to the Mess. Most days he could get one weak whisky as they were rationed to one bottle per officer per month and the bottle rated twenty-two small tots. Supper was at 1915 and he returned to the office at 2000. Usually he finished the days work by 2230 and so to his quarters.

Saturdays and Sundays were just like any other day. In theory every officer and other rank had one day off in every week for recreation but this did not apply in Edgar's case because the earliest he ever got off on his rest day was 1630 and that only occurred three times. His WO Chief Clerk kept an exact record of office attendance and after one six month period, showed Edgar had clocked up over of eighty four hours a week actually at his desk.

There was never any hour in the office during the eighteen months when he stopped sweating. If his elbow touched a piece of paper it stuck to it. It was necessary to hurry through the work to keep pace, even when working all day and part of the night.

He only had two days off duty during the whole period when he got a sharp attack of tonsillitis and the MO filled him up with M&B tablets.

In all those months he never wrote or received a private letter. When he arrived in Achimota the Brigadier and General Staff were all brilliant young regular soldiers. He was older than any of them. They nicknamed him 'Father'. After a while he was never called anything else; even the General used it sometimes when in a genial mood. Old age seemed to be creeping up on Edgar when on entering the anteroom one night before supper he was just in time to hear the Adjutant say to a newly arrived Major from England: "I'm sorry Sir you can't sit in that chair; that's Colonel Whitehead's chair."

Apart from the six weeks in the Civil Service in Gwelo in 1928 Edgar had never before worked in an office. The Army gave him a thorough training in efficient administration. Anybody who made a serious mistake was promptly returned to his unit, reverting to his prewar substantive rank. Delays were not tolerated. Without this experience Edgar could never have become an efficient Minister of Finance. Many times after the war he wished that as Minister he had the power to get rid of incompetent Senior Officers and promote keen young men, but Civil Service tradition was too strong to breach.

His eyes stood the strain of these long hours remarkably well. His deafness was no handicap. Everybody knew that he had been with the 4th Anti-aircraft Division in Britain. When Staff Conferences were held the Brigadier always said to Edgar: "Father, come and sit next to me or you won't hear a word; you damn gunners are always deaf."

During his time at Achimota Edgar reached the highest pitch of efficiency he ever attained in his life. He worked nearly as hard in his twelve years as a Minister in Rhodesia but never quite as hard; there were more distractions. His mind was never again quite so fertile in new ideas for solving seemingly insolvable problems.

Perhaps it is true one can only give of one's very best but once.

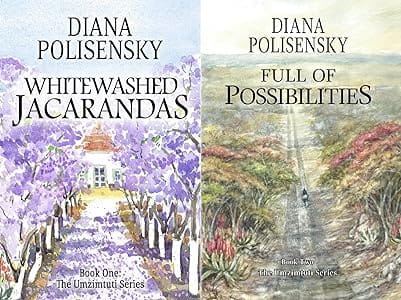

The historical novel Whitewashed Jacarandas and its sequel Full of Possibilities are both available on Amazon as paperbacks and eBooks.

Attention all Zimbabwe Readers! Hannah Rothwell of Pungwe Projects, 10 Stuart Avenue, Pomona, Harare can take book orders for Whitewashed Jacarandas and Full of Possibilities. Once Hannah places an order it is usually received from the UK within two weeks. Contact her at: PUNGWEPROJECTS@GMAIL.COM phone 0785 685 568. Find her on Facebook as Pungwe Projects or on Instagram as pungwe_projects.

The books are inspired by Diana's family's experiences in small town Southern Rhodesia after WWII.

Dr. Sunny Rubenstein and his Gentile wife, Mavourneen, along with various town characters lay bare the racial arrogance of the times, paternalistic idealism, Zionist fervor and anti-Semitism, the proper place of a wife, modernization versus hard-won ways of doing things, and treatment of endemic disease versus investment in public health. It's a roller coaster read.

References:

- Sir Edgar Whitehead's Unpublished Memoirs, Rhodes House, Bodleian Library, Oxford University, by permission.

- Photo credit: Source Unknown, inherited family photo (Family of Arabella Birdperson) - Inherited family photo (Family of Arabella Birdperson)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:General_Sir_George_J_Giffard.png