48th Air Dispatch

Edgar Whitehead arrived at the 48th Air Dispatch HQ Camp on a cold and wet summer's evening. Isolated, some distance from the nearest village it was a tented camp in a wet field somewhere in Gloucestershire.

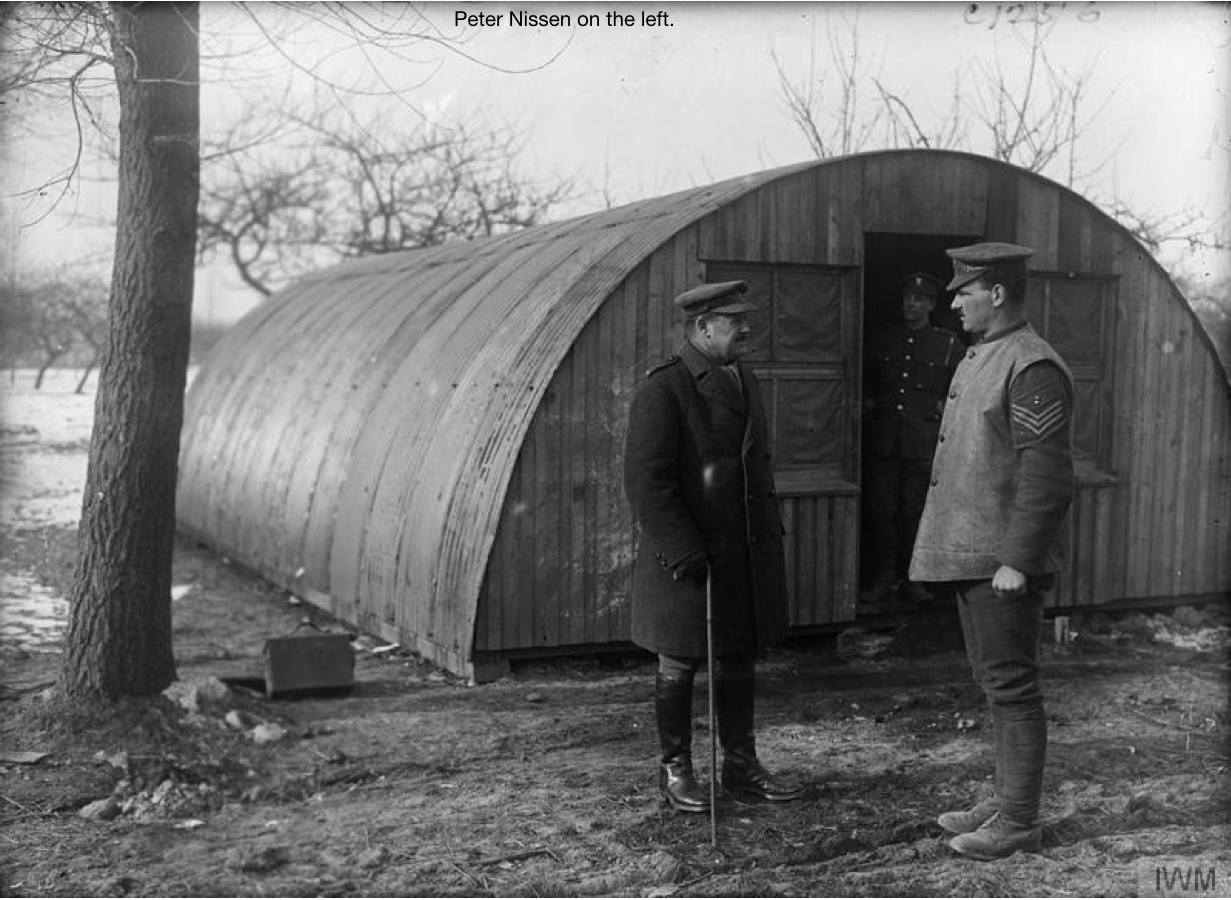

The tents leaked like sieves and had no floor boards. The Mess was a marquee and the anteroom a loose box. The offices were in a Nissen Hut in another field a short motor drive away.

Like Edgar's arrival at Achimota, his coming was not altogether welcome. The unit had been training assiduously for six months for their part in the Normandy operations and had reached a high pitch of efficiency. They did not warmly receive a new Second-in-Command who knew absolutely nothing about their highly specialized work. He wished heartily the WO had posted him a month earlier so he could've got a grasp of the duties before they started operations.

The units operational Companies were scattered over South Gloucestershire and North Wiltshire, near the nine RAF airfields from which they were to operate.

The total strength of 48th Air Dispatch was about three thousand. The RAF unit working with them had about three hundred Dakotas. Each Dakota had removed the door and could carry ten five hundred pound loads resting on rollers which enabled them to be pushed easily out of this space. So in one operation the three hundred Dakotas could, theoretically, drop seven hundred and fifty short tons of stores anywhere in Normandy within ten seconds. Four of their men were required to fly in each aircraft. In addition they required sufficient three ton lorries and men to load supplies from the roadside dumps, deliver them to the nine airfields, make them up into five hundred pound loads, load the aircraft scientifically so that the aircraft was neither nose nor tail-heavy, and affix the parachutes. Speed was of the essence and a very high degree of organization and training was necessary to achieve it. Their men had to be able to repack parachutes and also pack 'bomb cell containers' when for more distant objectives the RAF used Short Stirling bombers to drop equipment to the French Underground as far away as Savoy.

The morning after Edgar's arrival, the CO interviewed him outlining his duties which included taking responsibility as Administrative Officer for thirty thousand tons of assorted stores dispersed on the grass verges of the some thirty miles of minor roads. He was issued with a Staff Car and the driver's batman, who had served in the unit since its formation and knew the shortest way to all Company HQs and stores dumps. He was a staunch Communist who read the Daily Worker every morning but this was unimportant in 1944 when the Friends of the Soviet Union were headed by Lady Churchill. Every morning he brought Edgar's morning tea under weeping skies and opened the conversation by saying "Your tent is leaking as much as mine, Sir."

The reply was a gruff, "More."

He then would look at the puddle on the floor and the wet ground sheet over the blankets and say, "Pr'aps you're right, Sir."

Edgar had only been with the unit for a few days before D-Day. Everyone waited anxiously for the first call for their services. Their function was to replace by parachute any stores or ammunition which might be sunk on their way across the Channel or destroyed on the beaches. To this end they had their own wireless truck outside the Nissen hut in direct contact with 21st Army Group HQ. The landings were so successful that for the first day or two there was no request for their services! The first call on their organization was for a supply of Army forms.

As the Campaign in Normandy progressed the demands on them increased and more and more drops were made. It became the practice for some of the officers at HQ to accompany operational flights until the CO clamped down on the practice when he arrived one morning to find most of his officers on the wrong side of the Channel.

A big exercise was devised to test their capabilities. They were to drop one day's full requirements of rations, POL (Petroleum, Oil, Lubricants) and ammunition to the 52nd Division in a dropping zone on the Wiltshire Downs. The WO was anxious to see the new system at work. The Quarter-Master General arrived, together with other Generals and a charabanc with thirty-two Brigadiers. It was a dreadful day with low cloud and heavy rain. Edgar was made Chief Umpire for the exercise. The Quartermaster-General to the Forces (QMG) and other visitors took their places on a hill overlooking the dropping zone, but the charabanc carrying the Brigadiers was late. According to orders, Edgar met it at one end of the dropping zone but the Senior Brigadier told him, "It's such a wet day I think we will get a very adequate view from the charabanc."

"The General has given me categorical instructions that you are to join him on the hilltop."

With much grumbling the party trudged up the hill in the pouring rain. Edgar then told the driver to take his vehicle out of the dropping zone.

The driver countered, "The senior Brigadier has expressly forbidden me to move the vehicle."

Edgar warned, "You better at least get yourself half a mile away."

Shortly afterwards, the drop began. It was most impressive. Cotton parachutes were used for dropping stores and some always failed to open or turned inside out. These were called 'Roman Candles'. Edgar's duties kept him on the dropping zone. He ran as much that day as when playing rugby. Each time a parachute failed he gauged where the load would fall and took evasive action. One of the first Dakotas produced a 'Roman Candle" carrying a load of mortar bombs which went straight through the charabanc roof, wrecking it.

Edgar was in trouble with everybody. His CO wanted to know why he permitted the vehicle to remain in the danger zone. The Brigadiers wanted to know how to get back to London. The Colonels who heard how he insisted on the Brigadiers marching up the hill, asked what he meant by stopping promotion.

The exercise was very impressive though there were some defects in administration, partly due to Edgar's inexperience. He and his CO were called up to the WO for a post-mortem to see how the technique could be improved. They had a succession of flying bombs overhead and so the discussion was apt to languish as one came close.

Shortly after this General Horrocks visited as they were to drop his Corps in Normandy. He wanted to see for himself their capabilities. After his CO closeted with Horrocks for a long time he finally introduced his officers.

Horrocks asked Edgar, "Where do you come from?"

Edgar said, "Rhodesia."

Horrocks threw both hands in the air and said, "I have been in the Desert, Sicily, Italy and Normandy and every time I find a man doing a key job, he's always a Rhodesian! You've only got two men and a boy how do you do it?" He went on in the kindest way to mention some of Edgar's farming friends he'd met in the Desert.

It was only afterwards Edgar realized this was probably the first rehearsal for the Arnhem operation (Operation Market Garden).

The historical novel Whitewashed Jacarandas and its sequel Full of Possibilities are both available on Amazon as paperbacks and eBooks.

These books are inspired by Diana's family's experiences in small town Southern Rhodesia after WWII.

Dr. Sunny Rubenstein and his Gentile wife, Mavourneen, along with various town characters lay bare the racial arrogance of the times, paternalistic idealism, Zionist fervor and anti-Semitism, the proper place of a wife, modernization versus hard-won ways of doing things, and treatment of endemic disease versus investment in public health. It's a roller coaster read.

References:

- Sir Edgar Whitehead's Unpublished Memoirs, Rhodes House, Bodleian Library, Oxford University, by permission.

- Photo credit: